In January 2015, The Feminist Wire and the University of Arizona will co-host the Black Life Matters conference in Tucson, Arizona. Free and open to the public, the event aims to build on the visionary work of Black Lives Matter and a surge of activism emerging from the murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. We understand that our event, like many others, is not an isolated occasion but rather part of an ongoing, vital conversation about anti-Black state violence in the United States (and globally).![Black Lives Matter]()

Patrisse Cullors and Darnell L. Moore both will participate in the January conference (along with many other fantastic and formidable activists, scholars, and artists). I spoke with them on November 22—the day before the anticipated announcement out of Ferguson about the indictment—about their work and the Black Lives Matter movement. In particular, I wanted to discuss the relationship between the movement Black Lives Matter and the conference Black Life Matters, as our various publics have noted the overlap. Both terms are deployed somewhat interchangeably in various media, and the latter is sometimes used without a discussion of its important genealogy.

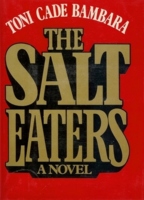

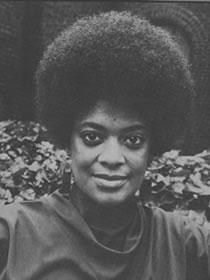

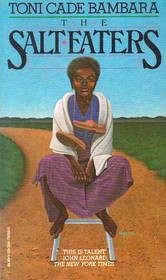

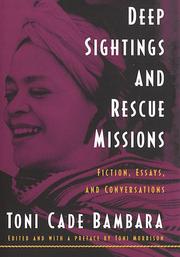

It is fitting that this interview with Patrisse and Darnell follows TFW’s monumental, inspiring, and urgently needed Toni Cada Bambara forum, curated by associate editors Aishah Shahidah Simmons and Heidi R. Lewis. In their afterword to the forum (which includes links to all the contributions), Aishah and Heidi write, “The ending of this forum is also the continuation of our work at TFW and beyond…Past is prologue.” Indeed.

Monica: Why are you involved in Black Lives Matter?

Patrisse: I feel like it changes every day. I want to give an authentic answer, not a rhetorical one. What I’ll say this morning is that I’m involved because my life depends on it. Because it’s one of the most healing calls I’ve ever experienced in my lifetime. I’m involved in Black Lives Matter because it pushes me to think creatively and to think about what actions, what kind of strategy, what tactics can come from a call like Black Lives Matters.

Darnell: Because I feel like I have to be. It’s a really important political intervention. Not only in its naming, but we shouldn’t have to say in 2014 that the lives of Black people matter. But given anti-Black policies and the ways that those policies allow for the deaths of Black people, extrajudicial or not, in so many ways we are told that our lives and bodies don’t matter. The other thing I’ll say is that this is a movement begun by three Black queer women after Trayvon Martin’s murder. Most of these social movements are only thought to be organized by cisgender men, at least that’s who we see. And it means something that Black queer women are at the forefront of leading this, leading us. It’s important for me to be part of something more intersectional and inclusive of a range of Black bodies and experiences that are often left out and marginalized in Black justice work.

Monica: Can you describe the nature of your involvement in the movement?

Patrisse: As one of the co-founders of Black Lives Matter, I think that I provide leadership around…well, that is a really good question. What is the nature? It’s so collaborative. I think, the nature of my involvement: yes, co-founder. I like to also say co-visionary. So, envisioning what this political project is, what this network is. I’ve been working with a lot of potential chapters across the country and in Canada; folks in Toronto just created a Black Lives Matter Facebook page. I want to talk to them a bit more, because they have an interesting relationship to Black Lives Matter. They are pushing the U.S. in a particular way about anti-Black violence; the Black folks in Canada have our backs! I know there are issues in Canada too for black people. So I’m trying to think about these potential chapters across the country, and trying to think about the relationship between the national and regional movements.![Black Lives Matter]()

The other piece of this involvement is: how does Black Lives Matter really push the narrative that all Black lives matter? Darnell, Alicia [Garza], and I are in conversation with TWOCC [Trans Women of Color Collective], led by Lourdes Ashley Hunter. We have reached out to Black trans women about Black Lives Matter. I have reached out to them, giving Ashley a call today, in fact, to talk about inclusion. As the leadership of this movement, we’re trying to push ourselves to be responsible that it is not just Black cis folks leading it, but trying to figure out what are we calling for, how to not just get stuck in the narrative of ‘save the life of young straight black cis men.’ Though this is important. So the nature of the work is about shaping, trying to shape this network politically, in ways that are aligned with ourselves given that we’re all queer. And also aligned with our vision for how much we love all Black people.

Darnell: My involvement began with organizing the Black Lives Matter ride to Ferguson after Michael Brown’s death. It wasn’t planned. I got a text early one morning from Darius Clark Monroe, a filmmaker who lives in my neighborhood. It was about four in the morning. I was up; I couldn’t sleep either. Darius and I were both thinking about Mike Brown’s death, which was haunting us. We said we should go there, to Ferguson; we were going to drive, get some folks together and just head there spontaneously that weekend. But, we decided to plan, to get a larger plan in place and a larger community. We also wanted to connect with people in Ferguson first. The next day, I was on a conference call with Patrisse, Alicia Garza, dream hampton, and Thandisizwe Chimurenga to discuss the Theodore Wafer case (Wafer murdered Renisha McBride), after he had been found guilty. We were discussing movement work, prison abolition, and anti-Black police and vigilante violence. I said to Patrisse after the call that I was planning to organize a ride to Ferguson. And noted that we should do it together. She agreed. So we decided to do it together.

![Black Lives Matter]() We used our lists of email addresses and various networks to pull people together. We reached out to our friends, really. Within 24 hours, we had a person on board that was going to handle administration, somebody to handle media stuff, and so on. Within a few days, we had a national team of volunteers. Patrisse mentioned that we already have this Black Lives Matter hashtag in place and that we should use it. Alicia [Garza] gave us the passwords to all the social media outlets for the hashtag, and before we knew it, we had some 500 people across the country riding to Ferguson! All were organized by volunteers from within the U.S. and Canada. And in their own communities, they are still organizing in various ways as volunteers. There is national work, and then localized work that folk can commit to in their own spaces.

We used our lists of email addresses and various networks to pull people together. We reached out to our friends, really. Within 24 hours, we had a person on board that was going to handle administration, somebody to handle media stuff, and so on. Within a few days, we had a national team of volunteers. Patrisse mentioned that we already have this Black Lives Matter hashtag in place and that we should use it. Alicia [Garza] gave us the passwords to all the social media outlets for the hashtag, and before we knew it, we had some 500 people across the country riding to Ferguson! All were organized by volunteers from within the U.S. and Canada. And in their own communities, they are still organizing in various ways as volunteers. There is national work, and then localized work that folk can commit to in their own spaces.

I’m so tired today because last night I was with folks from New York and New Jersey who are doing community work and building actions. I just now got a text from a friend that says, “I need to be around my people tomorrow.” With this indictment decision coming down, you need another to be held, you need embraces, to be angry, to breathe, to be creative, and to think about solutions with folks who care about you. This movement has brought a wonderful family and community structure, bringing together people from a range of sexualities, gender expressions, different ages.

Recently, folks have been importantly attending to inclusion of trans women and trans men; the last two weeks BLM has facilitated Twitter chats, doing work with the Trans Women of Color Collective. We are trying to make racial justice work more inclusive of trans women issues. And it’s important to note, we are all queer leaders. This is so important, not only because it shapes our politics, which is why we’re pushing ourselves to be more expansive. We have been talking to TWOCC because there have been failures to be inclusive in the past. It is important in this conversation to say that we are queer. Patrisse and I have talked a lot about how Black queer, women’s, and trans voices are absolutely left out of national conversations about Black people’s lives. So it is important to reiterate our own queerness. Patrisse and I have spent a lot of time with young queer leaders in Ferguson; we have spent a lot of time providing them with support.

Monica: What does Black Lives Matter have to do with Black Life Matters? Is this a movement that is bigger than each event?

Patrisse: This is a good question, mostly because there have now been so many things using that term—academia has done conferences, folks are using the slogan. There are two things. There is the slogan Black Lives Matter that has been utilized in some of the most amazing ways, and then some not so amazing ways. The Atlanta Democratic Party put it on their brochure—did you see this, Darnell? There are interesting things we’re all trying to figure out, and the slogan is out there and being used. Lots of folks have seen it, it’s gone viral, even the most sheltered white people have seen it. So now we’re trying to figure out, what is the actual political project?

I can only imagine during the 1960s, when Black Power emerged, that the phrase went viral; folks were using it, that’s what happened. Then, there were actually different political projects that grounded Black Power in actual work. Black Lives Matter is in that place where even with this conference, I’m interested in being in spaces that are being elevated by folks that work closely with and alongside of the people who are showing up. The conference should reconnect with Black Lives Matter folks we rode with and haven’t seen; we should make space for Darnell, myself, other Black Lives Matter folk to sit and be with each other, to strategize.

![Black Lives Matter]()

Source: Black America Uncensored

I’m also very interested in how folks are going to use the slogan. UC Berkeley had a Black Lives Matter conference after the ride; I emailed them, to let them know before Alicia came out with her story of Black Lives Matter – she is a really cool convener, brings people together. But the UCB folks didn’t reach out to us, I reached out to them. More often now folks are reaching out to myself and Alicia and Darnell; especially more now that Alicia has written her story. And folks tell others to talk with Alicia [Garza], Opal [Tometi], and me. So people use the slogan, but in ways that are not necessarily connected to the other work. We want to change that.

Darnell: The movement is bigger than each event! Black Lives Matter as both spirit and movement was catalyzed by three women, Patrisse, Opal [Tometi], Alicia [Garza] – that is, all of these actions and expressions are not only about solidarity, but also various community commitments, in the spirit of ameliorating and destroying anti-Black structures. All in the same spirit, all in the same tradition. There are these various expressions of Black solidarity, of Black liberation and freedom, that now have a place to call home.

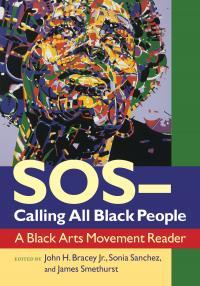

And this is not at all disconnected from a range of other movements. In our TFW forum on Toni Cade Bambara, Cara Page wrote about the response to the Atlanta child murders; might this have been a precursor or movement in the same tradition of Black Life Matters today? Black Lives Matter is innovative, but it is not disconnected from all the movement work that has been going on forever. We are purposely saying that this iteration of Black struggles must be inclusive of all Black lives. And that is different in some ways. When we say Black lives, we mean all Black lives: women, cis and transgendered women, queer, undocumented, disabled Black folk. This iteration is pretty phenomenal.

Monica: Why do you want to participate in the Black Life Matters in January 2015?

Darnell: I have no choice…that’s not even an issue. I am here sitting with my stomach in knots because of this impending verdict that’s going to come down regarding Darren Wilson. Somebody just texted me as I am talking to you, what’s the update? So many people are on edge. I spent Wednesday night trying to find a lawyer for a friend of mine, who had a ring on that looked like it could be a weapon. He’s a photographer, and he was wearing a ring that he can wear over two fingers. I tried to find a lawyer for him, because he spent the night in jail. Mike Brown’s death is not disconnected from the mundane forms of police profiling and brutality Black folk encounter everyday. It’s about Andre my friend being arrested because he looks suspicious. I have no choice. I’m tired. I’m really, really tired and I want to see things change. The law that makes it possible for my friend to be stopped, the law that says if the police have a sense of you having a weapon of any kind, including clothing, they can stop you. That law has to be changed.

Patrisse: I’m not even sure how to answer that question. What does it mean? Like Darnell, I have no choice.

Monica: If you could describe in one phrase or sentence what’s been happening post-Ferguson, what would it be?

Patrisse: Black excellence. I’ve seen the folks in St. Louis go from being tear-gassed, in utter chaos, with lots of splintering, to moving toward some deep and profound goals for themselves and Black people across the country. The level of leadership from folks who have never been leaders, the level of clarity is amazing. I also want to say that this movement allows for Black folks across the country, from those of us who have already been talking about this, for Black folks to be reborn and to push themselves to show up for Black people, and to show up for themselves.

![Black Lives Matter]() Darnell: I don’t want to use the term movement (though, I think we are in the midst of one), because I think it’s something different. There are ripples. Many of us are awake. The alarm clock has gone off again. And it has really awakened the conscience of a lot of people, and not just Black people either. The word I’ve been using is animated, maybe activated; because it’s easy to fall asleep, particularly under neoliberalism. Neoliberalism, capitalism is meant to keep us asleep; to give us the things we need so we feel good. Give somebody an iPhone, and all of a sudden we feel like we’re okay. But on that iPhone, you can now see a picture of a Black body laying in the street for more than four hours. Suddenly you see what’s happening, you can’t be comfortable in the belief that racism is over. Women’s bodies are not safe. You can pretend that trans women are not being killed; but then you wake up, and that trans woman’s body is right there before us in social media. As we talk, Islan Nettles’s murderer is out of jail, he wasn’t arrested. We have to wake up.

Darnell: I don’t want to use the term movement (though, I think we are in the midst of one), because I think it’s something different. There are ripples. Many of us are awake. The alarm clock has gone off again. And it has really awakened the conscience of a lot of people, and not just Black people either. The word I’ve been using is animated, maybe activated; because it’s easy to fall asleep, particularly under neoliberalism. Neoliberalism, capitalism is meant to keep us asleep; to give us the things we need so we feel good. Give somebody an iPhone, and all of a sudden we feel like we’re okay. But on that iPhone, you can now see a picture of a Black body laying in the street for more than four hours. Suddenly you see what’s happening, you can’t be comfortable in the belief that racism is over. Women’s bodies are not safe. You can pretend that trans women are not being killed; but then you wake up, and that trans woman’s body is right there before us in social media. As we talk, Islan Nettles’s murderer is out of jail, he wasn’t arrested. We have to wake up.

Monica: Tell me what you see five, ten years from now in terms of ‘black life matters’? What have we gained?

Patrisse: That’s so good. I’ve been thinking about this a lot, the 5-10 year plan. I hope in ten years, I hope in five years, that we’ve been able to develop a strong enough narrative that really pushes the debate. I’m a firm believer that you have to win the battle of ideas around the world, because culture shifts that way. Then you have to do the major policy work. But if you do the major policy work without shifting ideas, then you’ve not won. With the debate about Black Lives Matter, within five years I’d like to see some really beautiful campaigns led by all Black lives, that are funded in a way that makes them sustainable. I’d like to see major policy around decriminalizing Black lives, including reducing the law enforcement budget (one of our demands). I think this is something we can win in five years.

In ten years, I’d like to see some law enforcement agencies be disbanded or abolished, as well the development of a national network of families and victims working together in tandem, pushing for reform in their own cities. Either getting rid of police departments or having some serious checks and balances. With a reduction of law enforcement money, we can then be putting it back into Black communities. We need a new vision for jobs for Black folks, housing, healthy food. In ten years, I’ll be 41 years old; I really want all of this to happen. If it doesn’t, I’m outta here.

Darnell: Policy changes, legal changes, structural changes are important; but if we don’t change mindsets, ideologies, discourses—if folks don’t look at us and see us as humans, as worthy of living, as deserving of wellbeing—then I don’t think things will change. My hope is that in ten years, the Black people will be able to recognize that we do deserve to live, to survive. And that the state agents will recognize this, too. Until we can recognize this, things won’t change. Having laws in place doesn’t make us any more thoughtful about lives. I’m hopeful for mind-change, for our hearts to be expanded. And that in our social movements, we won’t only focus on the needs of those in the center of the power; that our movements will begin with those at the margins. We haven’t gotten there yet, and yet this is vitally important.

To register for the Black Life Matters conference, which is free and open to the public, visit the website.

______________________________________

![Black Lives Matter]() Patrisse Cullors is a native born Angeleno and an artist, organizer, and freedom fighter. She is the founder and executive director of Dignity and Power Now, and is building a coalition to implement permanent civilian oversight of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. Follow her on Twitter at @osope.

Patrisse Cullors is a native born Angeleno and an artist, organizer, and freedom fighter. She is the founder and executive director of Dignity and Power Now, and is building a coalition to implement permanent civilian oversight of the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. Follow her on Twitter at @osope.

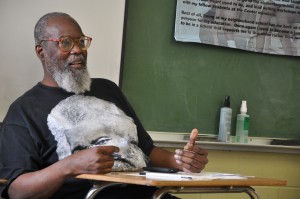

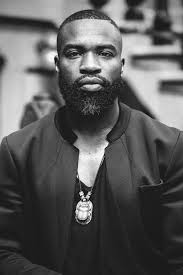

![Black Lives Matter]() Darnell L. Moore is a managing editor of The Feminist Wire and a writer and activist who lives in Brooklyn, NY. He is a faculty member in the Africana Studies program at Vassar College. He and Patrisse Cullors were co-organizers of the Black Lives Matter Ride to Ferguson, Missouri. Follow him on Twitter at @Moore_Darnell.

Darnell L. Moore is a managing editor of The Feminist Wire and a writer and activist who lives in Brooklyn, NY. He is a faculty member in the Africana Studies program at Vassar College. He and Patrisse Cullors were co-organizers of the Black Lives Matter Ride to Ferguson, Missouri. Follow him on Twitter at @Moore_Darnell.

The post Black Lives Matter / Black Life Matters: A Conversation with Patrisse Cullors and Darnell L. Moore appeared first on The Feminist Wire.